Welcome to the Research Corner. This is our newest feature for publishing articles about research carried out predominantly on salmonids (though you can expect a curve ball every once in a while) and the challenges they are facing, in order to help people better understand and appreciate our aquatic ecosystems – and hopefully work with us to protect and conserve them now and in the future.

Here you will find research that is being carried out nationally and internationally, but also our own research.

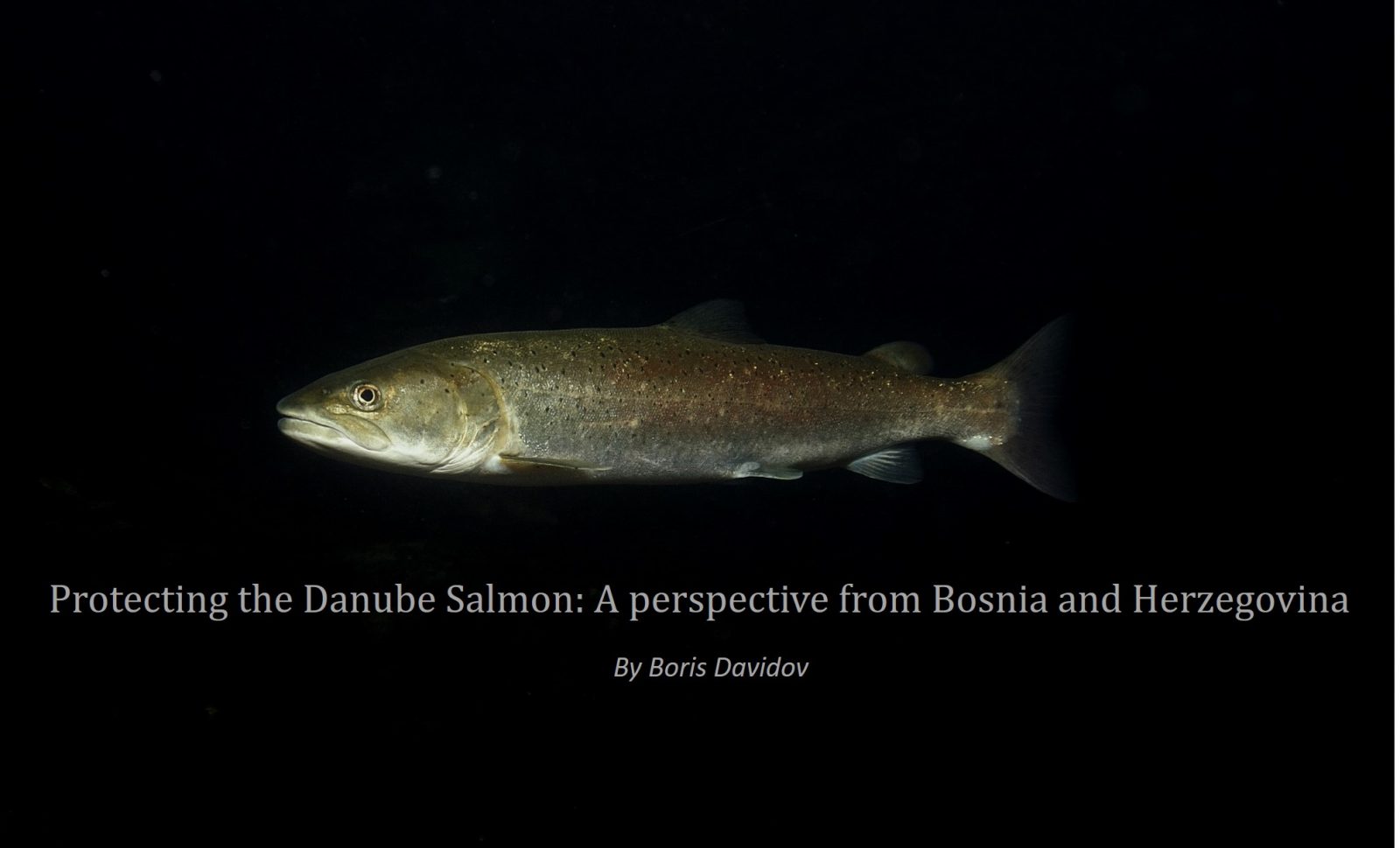

The spectacular river Una, with its emerald green waters gushing through canyons and down waterfalls, flows through the western part of Bosnia and Herzegovina and forms a natural national border between Bosnia and Croatia. It is home to the Huchen (Hucho hucho), or Danube salmon, one of the most iconic and enigmatic European salmonids, providing a draw for many fly fishers wanting to measure their skill against these big fish.

My team and I, the Society for Research and Protection of Biodiversity, are based in Bosnia and Herzegovina and are working on the river Una to conserve fish by carrying out research, which will hopefully, ultimately bring about better protection for these emblematic fish.

On the river Una we have three native species of salmonids, namely Danube salmon or Huchen, Grayling and Brown trout and one invasive species, the Rainbow trout. The main problem salmonids are facing in our river is overfishing and poaching. For the last 15 years, people have used fishing as a way of earning a living along most of our part of the river, even though it is prohibited by law. Very bad practical protection has resulted in some of the species being in a very bad position – with some populations down 90-95%.

In terms of the whole river system, we have also always had conflicts with small hydro power plant projects. Hydropower plants have great negative impacts on fish species in rivers. They tend to change morphological structure, adding more sand and soft particles and therefore making it muddier and in those conditions most of the fish species are unable to spawn. Hydropower plants also impact water temperature, in turn impacting all life in the river – from water insects, which are an important main food source of most of the fish species, to the fish themselves, as well as the abundance of oxygen. Natural migration routes are blocked and the species have a hard time adapting to sudden changes in the environment, subsequently diminishing the abundance of the populations in the river. The last hydro project, planned in 2015, was withdrawn thanks to the help of local communities, ecologists and conservationists all around the country who objected.

For the last 4 years the team has conducted research on one of the most enigmatic and endangered species in Europe, the Danube salmon (Hucho hucho). The Danube salmon is the largest salmonid we have in European waters, growing up to 35kg and representing the top predator in the rivers it inhabits. The species’ native distribution is throughout the Danube drainage. They spawn between the middle of February to May on the graveled bottom of the river. Juveniles mostly feed on water invertebrates and the subadults and adults are mainly piscivorous, meaning they feed on other fish.

We are conducting our research of the population on a big river system in Bosnia for the first time. As part of this we used fly fishing and spinning to catch Danube salmon, collecting data, including length, weight, location and a photograph to allow us to identify individual fish.

This is possible because each individual has a specific number, shape and distribution of black spots on their head, which we use to distinguish between individuals of the population. Using this method, we can monitor the population and then use the data to influence government institutions and the general public, to better protect and conserve individual fish we have left. During our research we learned that these fish do not conduct big migrations, as previously thought, and that the adult fish are highly territorial. The migrations they do undertake during spawning are only to the closest area with shallow graveled bottom, medium flow and variable depth, which are perfect conditions for spawning. Therefore, once an area has been over fished, new fish are not immediately moving into the area that is no longer occupied. However, the expectation is that, while adults are less likely to move around, juveniles will still do so in search of their own territory – therefore recolonization will happen, but slowly.

This is possible because each individual has a specific number, shape and distribution of black spots on their head, which we use to distinguish between individuals of the population. Using this method, we can monitor the population and then use the data to influence government institutions and the general public, to better protect and conserve individual fish we have left. During our research we learned that these fish do not conduct big migrations, as previously thought, and that the adult fish are highly territorial. The migrations they do undertake during spawning are only to the closest area with shallow graveled bottom, medium flow and variable depth, which are perfect conditions for spawning. Therefore, once an area has been over fished, new fish are not immediately moving into the area that is no longer occupied. However, the expectation is that, while adults are less likely to move around, juveniles will still do so in search of their own territory – therefore recolonization will happen, but slowly.

The Una flows through several cities and each municipality governs its own part of the river. Upstream of our stretch we have one of the best and abundant places of the river in terms of wild fish species. This area is managed by the fishing society from Bosanska Krupa and is a catch and release zone. Due to that, they successfully managed to conserve and preserve the Danube salmon population in their area in the last decade. This healthy population is one of the big draws for tourism around the city of Bosanska Krupa.

The Una flows through several cities and each municipality governs its own part of the river. Upstream of our stretch we have one of the best and abundant places of the river in terms of wild fish species. This area is managed by the fishing society from Bosanska Krupa and is a catch and release zone. Due to that, they successfully managed to conserve and preserve the Danube salmon population in their area in the last decade. This healthy population is one of the big draws for tourism around the city of Bosanska Krupa.

The number of fish caught on Bosanska Krupa on an annual basis is up to 95% more compared to any other part of the river where conservation fishing policies are not in place. The difference is that catch and release is mandatory on that part of the river and that it is truly enforced by the fishing society, which had not been achieved previously. The fishing society also manages spawning regulations and has introduced a closed season during the spawning months – no fishing takes place throughout the entire part of the river while spawning is ongoing. The society in Bosanska Krupa also has a catch limit on the open water (the part of the river on which the fishermen can take fish out of the river for consumption) – 1 fish per year per fisherman. Contradictory to normal Bosnian law for open water stating that no fish can be taken which is less than 70cm in length, the society has pushed this size limit up to 90cm, which in turn improves the health of the population significantly.

We use the data from Bosanska Krupa to compare it to the average number of fish caught in other individual zones on an annual basis. We then use that data to compare it to the open water and see the fluctuations in number of fish caught.

Whether or not an area is effectively governed depends on the individual fishing societies. Along our stretch of the river we have been working on a protected area, which is now enforced as a 2km stretch of the river as a zone where no fishing takes place – a ‘no go zone’. The ‘no go zone’ came into action from the middle of 2018 and therefore it is expected to take a couple of seasons for the population to recover.

We have tried to contact the local fishing society and people who sell fish in order to generate an income to try and persuade them to make changes and show them that more money can be generated in the long run when a management system like the one in Bosanska Krupa is applied, but since peoples’ financial situation here often means they are living from day to day they are not interested in the long term gain.

We have tried to contact the local fishing society and people who sell fish in order to generate an income to try and persuade them to make changes and show them that more money can be generated in the long run when a management system like the one in Bosanska Krupa is applied, but since peoples’ financial situation here often means they are living from day to day they are not interested in the long term gain.

We cannot predict the future of these amazing fish yet, but we will continue to improve the habitat quality and attempt to enforce more protection to provide these fish with a fighting chance to repopulate our river.

About Boris Davidov

Boris Davidov is an ecologist and ichthyologist from Bosnia and Herzegovina. He spent the last decade in the Sharklab, an organization dedicated for research and conservation biology and ecology of cartilaginous fishes. He is also a member of Dizb (Society for Research and Protection of Biodiversity). Through the projects that started in 2015 he is actively involved in research and conservation of Danube salmon in the Una river. He is one of the first people to lead a team to research this endangered fish for a big river system in Bosnia and Herzegovina.